Testing Effect and Retrieval Learning

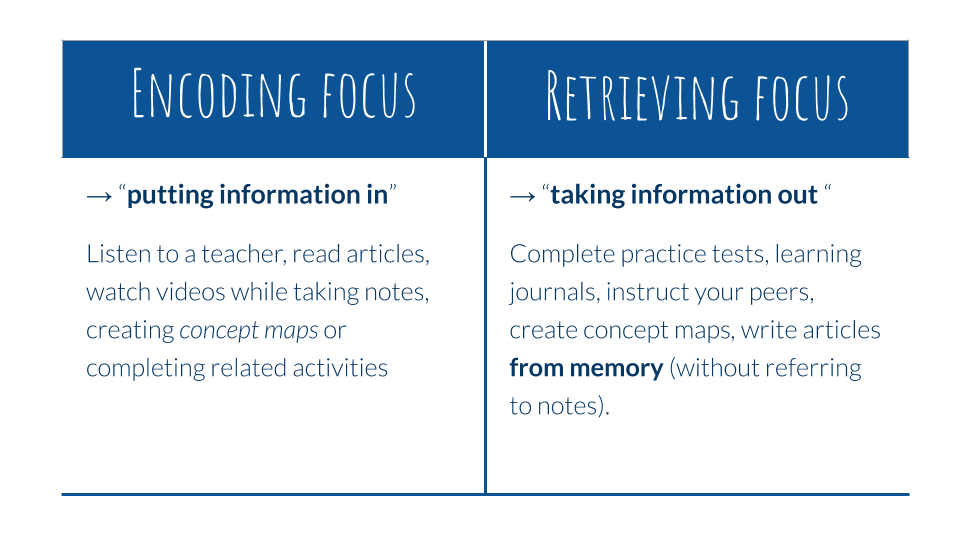

What type of activities have been shown to support durable learning in students? From a cognitive perspective, we can place learning activities into two broad categories: encoding activities and retrieval activities. Encoding related activities focus more on “putting information in” to long-term memory. Retrieval related activities focus more on “taking information out” of memory – i.e. practicing the extraction of information from our long-term memory. For example, when students listen to a teacher, read articles, watch videos, or create concept maps or write essays while looking at their notes, they perform encoding activities. These student actions are completed as part of putting information in memory accurately and elaborating on it. On the other hand, when students complete practice tests, write learning journals, instruct peers, or create concept maps or write essays from memory (e.g. without referring to their notes), they perform retrieval activities. As the student actions are completed without referring to their notes, they are required to retrieve the information from their memory system.

Empirical studies have found that students need to reconstruct memories and strengthen retrieval routes. A mix of encoding and retrieval activities are beneficial. As Bjork, Dunlosky & Kornell (2013) write, “to be a sophisticated learner requires understanding that creating durable and flexible access to to-be-learned information is partly a matter of achieving a meaningful encoding of that information and partly a matter of exercising the retrieval process.” But when comparing the efficacy of encoding versus retrieval types of activities, especially when reviewing material for tests, we see that retrieval activities are more effective in supporting durable learning. The results of such studies describe the testing effect. “Taking a test on material can have a greater positive effect on future retention of that material than spending an equivalent amount of time restudying the material, even when performance on the test is far from perfect and no feedback is given on missed information” (Roediger III & Karpicke, 2006a). The testing effect has been demonstrated in hundreds of studies since 1909 including studies on language learning, general knowledge, visuospatial materials, science, social science, statistics and in medical education. The studies have used real university exams, online testing, and in-class testing (Roediger III & Karpicke, 2006a). Below are two studies that demonstrate the benefits of retrieval learning (i.e. the testing effect).

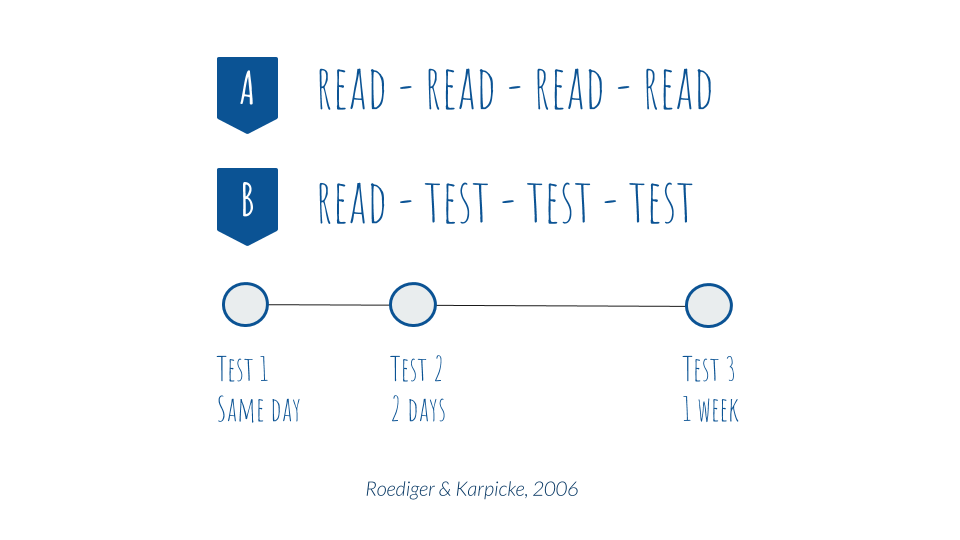

Study 1: Encoding vs. Retrieval Practice (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b)

Students studied two TOEFL texts and took three tests at different times. The first was an immediate test after the last learning session, the next was after a 2-day delay, and the third was after a 1-week delay. Group A studied the text four times (study-only). Group B studied the text once (7-min) and then took 3 free recall tests without feedback. In other words, the students in Group B read the text once and then wrote down all they could remember about the text 3 times without being able to see if their writing was correct or not. Both groups spent the same amount of time studying. The study-only group (Group A) performed better on the immediate test (81% vs. 75%). The retrieval group (Group B) performed better on delayed tests (56% vs. 42%). The benefits of retrieval activities became more apparent the longer the delay. “The repeated-testing condition recalled much more after a week than did students in the repeated-study condition (61% vs. 40%), even though students in the repeated-testing condition read the passage only 3.4 times and those in the repeated-study condition read it 14.2 times.”

Study 2: Encoding vs. Retrieval Practice (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011)

80 undergraduate students studied a science text and took a short-answer test (1 week later) with both verbatim and inference questions. Verbatim questions are recall questions of facts. Inference questions are more complex and require students to connect concepts within the text. Group A read the text and then created a concept map of the text. The concept map was created while reading the text. Group B read the text and wrote down all they could remember about the text (repeated twice) without referring to the text. There was almost a 50 percent increase for retrieval learning (M = 0.67) over concept mapping (M = 0.45) in conceptual learning in the test given a week later.

All in all, the type of learning activity we have students perform makes a difference. Interestingly, in Study 2 described above, even when the final test involved constructing a concept map, practicing retrieval during the original learning outperformed the group that practiced concept mapping (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011).

References

Testing Effect and Retrieval Learning

- Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual review of psychology, 64, 417-444.

- Roediger III, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006a). The power of testing memory: Basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspectives on psychological science, 1(3), 181-210.

- Roediger III, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006b). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological science, 17(3), 249-255.

- Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772-775.

Additional reading on the testing effect and retrieval learning

- Rawson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (2005). Rereading effects depend on time of test. Journal of educational psychology, 97(1), 70.

- Bjork, R. A. (1988). Retrieval practice and the maintenance of knowledge. Practical aspects of memory: Current research and issues, 1, 396-401.

- Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger III, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: do students practise retrieval when they study on their own?. Memory, 17(4), 471-479.

- Koriat, A., & Bjork, R. A. (2006). Illusions of competence during study can be remedied by manipulations that enhance learners’ sensitivity to retrieval conditions at test. Memory & Cognition, 34(5), 959-972.

- Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: How much is enough?. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140(3), 283.

- Roediger III, H. L., & Pyc, M. A. (2012). Inexpensive techniques to improve education: Applying cognitive psychology to enhance educational practice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(4), 242-248.

- Van den Broek, G., Takashima, A., Wiklund-Hörnqvist, C., Wirebring, L. K., Segers, E., Verhoeven, L., & Nyberg, L. (2016). Neurocognitive mechanisms of the “testing effect”: A review. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 5(2), 52-66.